This is the paradox at the heart of Dasa Mahavidya : Gesture, Form and the Feminine Divine, an exhibition that brings together the works of Krishnanand Jha (1947–2018) and Santosh Kumar Das. For centuries, the brush in Mithila painting has been held by women, who inscribed devotion, memory, and ritual on the walls of their homes. When men entered this tradition, they unsettled its gendered inheritance, creating both friction and possibility. For a man to paint the goddess in a woman’s art form is to transgress a boundary; to enter sacred terrain with one’s own hand is to rupture a lineage; and yet, in the act of surrender to the goddess, it is also a renewal, a reminder that Shakti transcends gendered authorship.

Dasa Mahavidya : The Ten Tantric Energy Goddesses of Hinduism

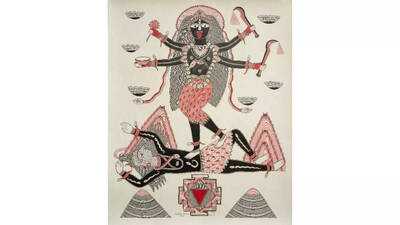

At the centre of the exhibition are the “Dasa Mahavidya” - the Ten Wisdom Goddesses of Tantra. These are not singular but plural, not reducible to one form but manifold embodiments of feminine power. Kali, the devourer of time; Tara, the guide across danger; Tripur Sundari , beauty incarnate; Bhuvaneshvari, mistress of the worlds; Bhairavi, the fierce one; Chinnamasta, the self-decapitated; Dhumavati, the smoky crone; Baglamukhi, the stunner of foes; Matangi, the outcaste musician; and Kamla, the lotus goddess of prosperity. These goddesses are believed to be manifestations of Goddess Parvati and are invoked for spiritual growth, empowerment, and the realization of the Supreme through practices like meditation, mantra chanting and devotional acts.

Collectively, they represent what Tantra insists upon: the feminine is not simply nurturing or benevolent but also terrifying, paradoxical, and boundless. She is creation and destruction, order and chaos, beauty and horror. To depict the Mahavidya is therefore not an ornamental act but a spiritual confrontation.

Krishnanand Jha: Lineage and Transgression

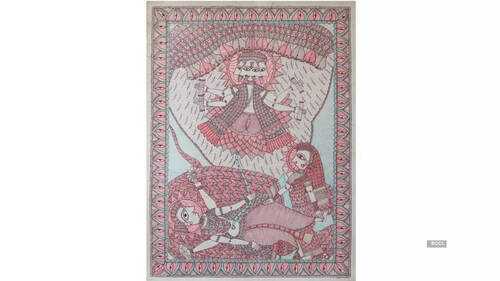

For Krishnanand Jha, painting the goddess was both natural and radical. Born into a family of tantric priests at village Harinagar, Madhubani, in Mithila, he was expected to continue priestly duties, steeped in ritual and mantra. Instead, he turned toward painting, making the sacred visible in a form traditionally reserved for women. His choice was a transgression: men did not paint Mithila walls, nor did they adapt its forms to paper for art markets. Yet Jha’s priestly inheritance gave him a unique authority to approach Tantric subjects with an insider’s vision.

His goddess of choice was often Chinnamasta, his family’s tutelary deity the goddess who severs her own head and drinks her blood even as she nourishes others. In her, Jha found the paradox of power and surrender, destruction and life-force. His line work is taut, ascetic, charged like a ritual diagram, while his color palette often red, black, and white resonates with tantric symbolism. In his compositions, the goddess is rarely still. She gestures, glances, and propels the viewer forward, as though the act of seeing itself becomes a ritual procession.

(In many traditions, the Dashavatara are understood as manifestations parallel to the Dasa Mahavidya, since both Vishnu and Kali/Parvati are believed to have arisen from the same primal energy of Adi Shakti and are often regarded as sibling forces. In this light, Krishnanand Jha’s fusion of the Dasa Mahavidya with the Dashavatara in a single frame above, stands out as a remarkable and original artistic vision)

In this way, Jha enacted a rupture: he brought esoteric tantric experience into the visual vocabulary of Mithila, turning a domestic art into a vehicle of mystical encounter. His paintings, collected internationally in institutions like LACMA, Los Angeles, USA and the Asian Art Museum, expanded the scope of what Mithila painting could hold.

Santosh Kumar Das: Symmetry and Renewal

Where Jha’s goddesses are in motion, Santosh Kumar Das’s goddesses stand firm. His Mahavidya are symmetrical, frontal, and commanding. Their stillness radiates a meditative energy, like yantras rendered in living form.

Das’s trajectory is equally layered. After studying English literature in Darbhanga, he pursued Fine Arts at M.S. University, Baroda. He returned to his ancestral village of Ranti, painting and teaching younger generations while bridging the rural and the global. His academic training gave him tools to engage with modern themes, while his roots kept him anchored in Mithila’s aesthetic language.

His “Dasa Mahavidya”, shown in this unique exhibition at Ojas Art Gallery, Mehrauli (Aug 23 to Sep 21), is an act of renewal. Each goddess is rendered with meticulous patterning, balanced symmetry, and a quiet but potent force. While deeply traditional, his paintings also converse with contemporary questions about identity, violence, ecology, and devotion. His earlier series on Krishna, Gujarat, and the Buddha testify to his ability to stretch Mithila’s idiom into new domains. Yet in the Mahavidya, he returns to the source the goddess as eternal sovereign.

Tantra and Mithila: Authority and Crossing

In Tantra, ritual authority has historically belonged to men, while in Mithila painting, aesthetic authority has long rested with women. When male artists like Krishnanand Jha and Santosh Kumar Das depict the Dasa Mahavidya, they stand at this interesting crossroads: inheritors of a male-dominated Tantric tradition and entrants into a women’s visual domain. Is this then a consolidation of male authority Tantric legitimacy grafted onto a female-authored art form or something more porous? Interestingly, several women painters too have painted the Mahavidya, thereby stepping into a ritual terrain usually closed to them. In this shared, unsettled space, neither gender holds uncontested power; the only true possessor of the field is the goddess herself the feminine, who here is not muse but master.

Masculine Interventions in a Feminine Tradition

The presence of Jha and Das raises the central question: what does it mean for men to paint the goddess in a form shaped and sustained by women? At first glance, it appears as intrusion an appropriation of a women’s space by male hands. Yet the works themselves tell a more complex story. Neither artist reduces the goddess to muse or fantasy. Instead, she emerges as master, sovereign, the axis around which artistic practice itself revolves. In this reversal, the gender dynamics shift: the male artist is not the possessor of the feminine image but its servant, its witness, its devotee.

In patriarchal art histories, women are often depicted by men as objects of beauty, desire, or allegory. But here, the feminine divine is depicted as commanding, terrifying, inexhaustible. The gaze is not owned by the painter; it is owned by the goddess, who looks back with unshaken force. Thus, these paintings embody transgression, rupture, and renewal. Transgression, because men step into a female domain. Rupture, because they alter the visual grammar of Mithila painting with tantric symbolism, symmetry, and contemporary themes. Renewal, because through devotion, they reaffirm the power of Shakti not diminished by male authorship but magnified by surrender to her sovereignty.

The Feminine as Master

This exhibition insists on a truth that is often overlooked in art discourse: the feminine is not muse but master. To encounter these paintings is not to consume an aesthetic image but to stand before a presence. Whether in Jha’s restless lines or Das’s meditative symmetry, the goddess is not passive. She commands attention, arrests time, and reorients the viewer’s gaze.This is what makes the exhibition so compelling. It is not simply about men painting in a women’s tradition. It is about how the goddess, when invoked with devotion, reorganizes every dynamic between artist and subject, viewer and image, tradition and innovation.In the works of Krishnanand Jha and Santosh Kumar Das, the feminine divine refuses domestication. She moves and she stills, she destroys and she nourishes, she terrifies and she consoles. Most of all, she reigns. Their art does not reduce her to muse or possession; instead, she emerges as sovereign the master before whom the artist himself must bow.By entering a space once considered exclusively female, these male artists performed a transgression. By reshaping its vocabulary, they enacted a rupture. Yet by invoking the goddess with such reverence, they offered renewal: a reimagining of Mithila painting where gendered boundaries blur but the power of the feminine remains absolute.The feminine is not muse but master. To stand before these paintings is to recognize that truth not in abstraction, but in pigment and line, in symmetry and gesture, in the commanding gaze of the goddess herself.

Authored by: Savita Jha

The writer teaches history at DU

Dasa Mahavidya : The Ten Tantric Energy Goddesses of Hinduism

At the centre of the exhibition are the “Dasa Mahavidya” - the Ten Wisdom Goddesses of Tantra. These are not singular but plural, not reducible to one form but manifold embodiments of feminine power. Kali, the devourer of time; Tara, the guide across danger; Tripur Sundari , beauty incarnate; Bhuvaneshvari, mistress of the worlds; Bhairavi, the fierce one; Chinnamasta, the self-decapitated; Dhumavati, the smoky crone; Baglamukhi, the stunner of foes; Matangi, the outcaste musician; and Kamla, the lotus goddess of prosperity. These goddesses are believed to be manifestations of Goddess Parvati and are invoked for spiritual growth, empowerment, and the realization of the Supreme through practices like meditation, mantra chanting and devotional acts.

Collectively, they represent what Tantra insists upon: the feminine is not simply nurturing or benevolent but also terrifying, paradoxical, and boundless. She is creation and destruction, order and chaos, beauty and horror. To depict the Mahavidya is therefore not an ornamental act but a spiritual confrontation.

Krishnanand Jha: Lineage and Transgression

For Krishnanand Jha, painting the goddess was both natural and radical. Born into a family of tantric priests at village Harinagar, Madhubani, in Mithila, he was expected to continue priestly duties, steeped in ritual and mantra. Instead, he turned toward painting, making the sacred visible in a form traditionally reserved for women. His choice was a transgression: men did not paint Mithila walls, nor did they adapt its forms to paper for art markets. Yet Jha’s priestly inheritance gave him a unique authority to approach Tantric subjects with an insider’s vision.

His goddess of choice was often Chinnamasta, his family’s tutelary deity the goddess who severs her own head and drinks her blood even as she nourishes others. In her, Jha found the paradox of power and surrender, destruction and life-force. His line work is taut, ascetic, charged like a ritual diagram, while his color palette often red, black, and white resonates with tantric symbolism. In his compositions, the goddess is rarely still. She gestures, glances, and propels the viewer forward, as though the act of seeing itself becomes a ritual procession.

(In many traditions, the Dashavatara are understood as manifestations parallel to the Dasa Mahavidya, since both Vishnu and Kali/Parvati are believed to have arisen from the same primal energy of Adi Shakti and are often regarded as sibling forces. In this light, Krishnanand Jha’s fusion of the Dasa Mahavidya with the Dashavatara in a single frame above, stands out as a remarkable and original artistic vision)

In this way, Jha enacted a rupture: he brought esoteric tantric experience into the visual vocabulary of Mithila, turning a domestic art into a vehicle of mystical encounter. His paintings, collected internationally in institutions like LACMA, Los Angeles, USA and the Asian Art Museum, expanded the scope of what Mithila painting could hold.

Santosh Kumar Das: Symmetry and Renewal

Where Jha’s goddesses are in motion, Santosh Kumar Das’s goddesses stand firm. His Mahavidya are symmetrical, frontal, and commanding. Their stillness radiates a meditative energy, like yantras rendered in living form.

Das’s trajectory is equally layered. After studying English literature in Darbhanga, he pursued Fine Arts at M.S. University, Baroda. He returned to his ancestral village of Ranti, painting and teaching younger generations while bridging the rural and the global. His academic training gave him tools to engage with modern themes, while his roots kept him anchored in Mithila’s aesthetic language.

His “Dasa Mahavidya”, shown in this unique exhibition at Ojas Art Gallery, Mehrauli (Aug 23 to Sep 21), is an act of renewal. Each goddess is rendered with meticulous patterning, balanced symmetry, and a quiet but potent force. While deeply traditional, his paintings also converse with contemporary questions about identity, violence, ecology, and devotion. His earlier series on Krishna, Gujarat, and the Buddha testify to his ability to stretch Mithila’s idiom into new domains. Yet in the Mahavidya, he returns to the source the goddess as eternal sovereign.

Tantra and Mithila: Authority and Crossing

In Tantra, ritual authority has historically belonged to men, while in Mithila painting, aesthetic authority has long rested with women. When male artists like Krishnanand Jha and Santosh Kumar Das depict the Dasa Mahavidya, they stand at this interesting crossroads: inheritors of a male-dominated Tantric tradition and entrants into a women’s visual domain. Is this then a consolidation of male authority Tantric legitimacy grafted onto a female-authored art form or something more porous? Interestingly, several women painters too have painted the Mahavidya, thereby stepping into a ritual terrain usually closed to them. In this shared, unsettled space, neither gender holds uncontested power; the only true possessor of the field is the goddess herself the feminine, who here is not muse but master.

Masculine Interventions in a Feminine Tradition

The presence of Jha and Das raises the central question: what does it mean for men to paint the goddess in a form shaped and sustained by women? At first glance, it appears as intrusion an appropriation of a women’s space by male hands. Yet the works themselves tell a more complex story. Neither artist reduces the goddess to muse or fantasy. Instead, she emerges as master, sovereign, the axis around which artistic practice itself revolves. In this reversal, the gender dynamics shift: the male artist is not the possessor of the feminine image but its servant, its witness, its devotee.

In patriarchal art histories, women are often depicted by men as objects of beauty, desire, or allegory. But here, the feminine divine is depicted as commanding, terrifying, inexhaustible. The gaze is not owned by the painter; it is owned by the goddess, who looks back with unshaken force. Thus, these paintings embody transgression, rupture, and renewal. Transgression, because men step into a female domain. Rupture, because they alter the visual grammar of Mithila painting with tantric symbolism, symmetry, and contemporary themes. Renewal, because through devotion, they reaffirm the power of Shakti not diminished by male authorship but magnified by surrender to her sovereignty.

The Feminine as Master

This exhibition insists on a truth that is often overlooked in art discourse: the feminine is not muse but master. To encounter these paintings is not to consume an aesthetic image but to stand before a presence. Whether in Jha’s restless lines or Das’s meditative symmetry, the goddess is not passive. She commands attention, arrests time, and reorients the viewer’s gaze.This is what makes the exhibition so compelling. It is not simply about men painting in a women’s tradition. It is about how the goddess, when invoked with devotion, reorganizes every dynamic between artist and subject, viewer and image, tradition and innovation.In the works of Krishnanand Jha and Santosh Kumar Das, the feminine divine refuses domestication. She moves and she stills, she destroys and she nourishes, she terrifies and she consoles. Most of all, she reigns. Their art does not reduce her to muse or possession; instead, she emerges as sovereign the master before whom the artist himself must bow.By entering a space once considered exclusively female, these male artists performed a transgression. By reshaping its vocabulary, they enacted a rupture. Yet by invoking the goddess with such reverence, they offered renewal: a reimagining of Mithila painting where gendered boundaries blur but the power of the feminine remains absolute.The feminine is not muse but master. To stand before these paintings is to recognize that truth not in abstraction, but in pigment and line, in symmetry and gesture, in the commanding gaze of the goddess herself.

Authored by: Savita Jha

The writer teaches history at DU

You may also like

Bengal assembly disruptions: Suvendu Adhikari suspended from remaining session; claims 'unethically forced out'

The Traitors fan favourites 'return' as 'iconic' new project announced

Premier League transfer window's biggest loser clear amid Liverpool and Arsenal debate

Delhi BJP slams Congress leader Pawan Khera over 'two votes'

Anne-Marie Duff shares heartbreak as brother diagnosed with dementia in 40s